|

If all surface temperatures are specified in a problem, the

results from Eq. (A-17) complete the solution. If qk is

specified for n surfaces and Tk for the remaining

N–n surfaces, then the n unknown surface temperatures are guessed,

the equations are solved for all q, and then the calculated qk

are compared to the specified values. If they do not agree, new values of Tk

for the n surfaces are assumed and the calculation is repeated until the

given and calculated qk agree for all Ak

with specified qk. Equation (11-8), expressed as a sum over

the wavelength bands, gives the required energy input to the medium for the

specified Tg.

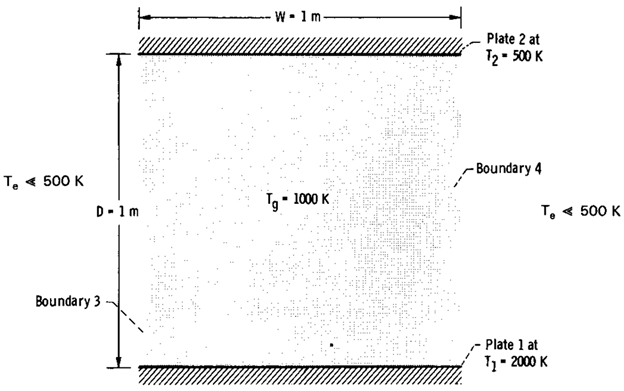

EXAMPLE A-2 Two black

parallel plates are D = 1 m apart. The plates are of width W = 1 m

and have infinite length normal to the cross section shown (Fig. A-9). Between

the plates is carbon dioxide gas at

As shown by Fig. A-9, the geometry is a four-boundary

enclosure formed by two plates and two open planes. The open areas are perfectly

absorbing (nonreflecting) and radiate no significant energy as the surrounding

temperature is low. The energy flux added to surface 2 is found by using the

enclosure equation (10-72) where k = 2 and N = 4. All

surfaces are black, ελ,j

= 1, so Eq.

(10-72) reduces to

The self-view factor F2–2 = 0 and Eλb,3

= Eλb,4

≈ 0, so this becomes

To simplify the example, it is carried out by considering the

entire wavelength region as a single spectral band. To obtain the total energy

supplied to plate 2, integrate over all wavelengths to obtain

By use of the definitions of total transmission and

absorption factors,

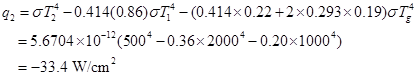

and so forth, q2 becomes

To determine

From factor 3 in Appendix C the F2–1 is

given by

Note that the largest contribution to q2 is

by energy leaving surface 1 that reaches and is absorbed by surface 2. Emission

from the gas to surface 2, and emission from surface 2, are small.

An alternative approach for this particular example is to

note that the term involving Tg in (A-20) is the

flux received by surface 2 as a result of emission by the entire gas. This can

be calculated from (10-114) using the mean beam length. Then

|